Why Is It Ironic That Arabs Taught Venetians the Art of Glass Blowing?

Illustration past Ellis Rosen

On a Friday nighttime this spring, I reported to the inaugural show at Fisher Parrish Gallery, in Bushwick. Some awfully cool looking folks were packed into the small white space. The tabular array was laid with 117 new examples of paperweights. Near none of them resembled the office accoutrement of last century, when open up windows and fans sent paper sailing through reeking cigarette fog. These were objet d'art. They ranged from the purely ironic (a hirsuite outgrowth) to the purely beautiful (concatenation links encrusted in sherbet crystals). Many were ineffable abstracts, and a few were just satisfying (animal figurines drilled into each other). "My life doesn't justify a paperweight," a girlfriend remarked. "My life isn't settled enough. Yous don't buy one until you think you're not going to move."

Paperweights had never struck me equally markers of stability. Only a month later, when I was laid off from the legacy media company where I worked for a print magazine, I surveyed my desk, picked upward a stack of our branded notepads and a handle of whiskey and thought, At to the lowest degree I don't accept to lug no paperweight.

Then Saturday came without Saturday's feel. In a vintage store, I drifted from taxidermy pheasants to a shelf staged with dusted curio, and there was a Murano blown-drinking glass paperweight. At its center, the softball-size bubble had a clear tubular band, within of which was a clear finial shape from which streaks of red sprayed in arches at 360 degrees. The thing was maybe five pounds? My fiancé establish me cradling it to my eye. "You're going to bring that home, aren't you," he said, significant: Did my foolhardy troth to paper in the age of new media know no bounds? The paperweight seemed to englobe our opposed perspectives: he thought it looked like a nasty vortex; I thought it looked like a vino fountain.

In 1495, a historian from Venice remarked, "But consider to whom did it occur to include in a fiddling ball all the sorts of flowers which clothe the meadow in Jump." He was referring to the glasswork techniques the Romans had picked up from the Egyptians. The results were not paperweights, not least considering the bottoms had non yet been shaved flat to prevent rolling. That was an evolution Paul Hollister, the late authorisation on paperweights, likened to "turn[ing] the Venetian pumpkin into Cinderella's gilded coach." (As a bonus, grounding the base removed the pontil mark, the scar from a glassblower'southward iron rod, and without a belly button, the orb seemed to come into the world by magic.)

Three and a half centuries afterward, in 1845, a glassmaker named Pietro Bigaglia showed off his "Venetian assurance" at the Austrian Industrial Fair, in Vienna. The primeval paperweight nosotros know of dates to that year. French fair-going glassworkers—wishing to goose their depressed industry—ran with the idea. It was merely three years earlier the February revolution and the creation of Napoleon's Second Republic. The time was right. With affordable paper and dependable mail service services, alphabetic character writing had become a newly popular pastime, and something had to keep those sheets in order. Glasshouses like Baccarat, Saint-Louis, Clichy, and Pantin revived ancient techniques such equally flame working, filigree, and millefiori, "thousand flowers" wrought from brightly colored glass canes; they as well perfected plant and brute motifs. These paperweights were useful, stylish, relatively inexpensive, and cheery (a way to go along flowers on desks even in winter), and their industry spread through parts of Europe. Immigrant glassworkers brought the trend and their know-how to America. But past 1860, the bauble-bubble was cooling off.

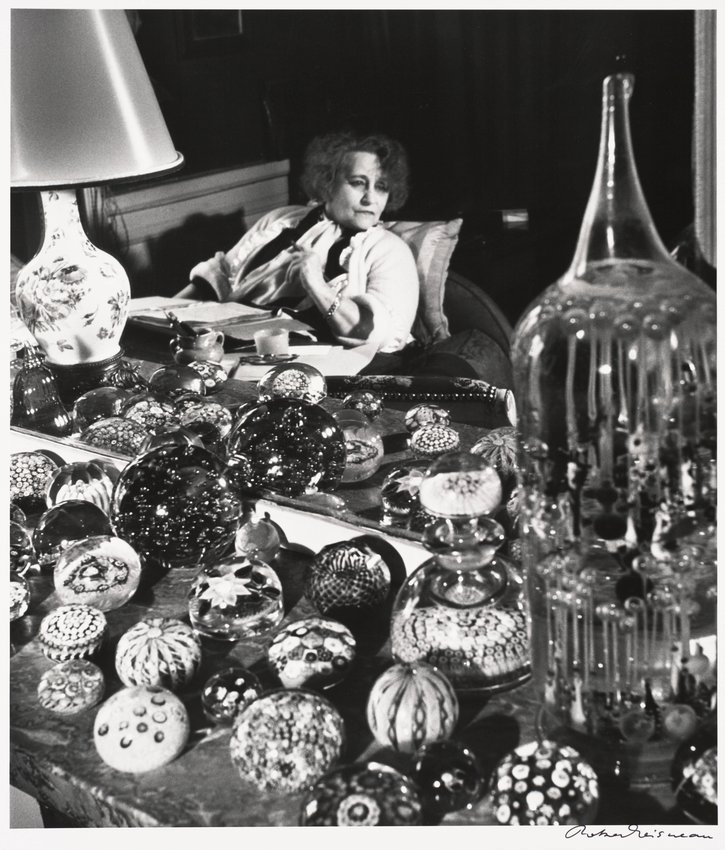

In the late forties, Jean Cocteau bundled for a young Truman Capote to have tea with Colette at her apartment in Paris. They did not manage to talk over literature; instead, Capote was moonstruck by the Frenchwoman's collection of valuable antique paperweights, which she called "my snowflakes":

At that place were possibly a hundred of them covering two tables situated on either side of the bed: crystal spheres imprisoning green lizards, salamanders, millefiori bouquets, dragonflies, a basket of pears, butterflies alighted on a frond of ferns, swirls of pink and white and blueish and white, shimmering similar fireworks, cobras coiled to strike, pretty niggling arrangements of pansies, magnificent poinsettias.

Madame Colette, with some of her paperweights, in 1950. © Robert Doisneau.

Colette suggested she might take them with her in her coffin, "like a pharaoh." When she gave a Baccarat with a single white rose inside to Capote, he defenseless the fever. He sought paperweights at auctions in Copenhagen and Hong Kong. In one case, he establish a 4-thousand-dollar weight in a junk shop in Brooklyn for which he shelled out just twenty bucks. In East Hampton, he successfully bid seven hundred dollars for a millefiori ("the real thing," "an electrifying spectacle") worth seven grand.

At home, my weight immediately found its apply. When you are a paperweight, y'all take one task, and it is so like shooting fish in a barrel. In theory, whatsoever lousy rock could do information technology: be heavy (drinking glass, crystal, marble, brass, and statuary accept been standard issue), exist flat-bottomed (spheres, pyramids, cubes, and discs tend not to topple), and sit pretty (on this last point, common geology would fail). If y'all can do that, yous are doing great. Layoffs still involve paperwork, which, one time printed, mostly has to go notarized and posted; such documents tin stagnate on your desk-bound, forth with odd to-practise lists, tear sheets, bills, and greeting cards. But I institute none of it was to be hands ignored or mislaid when it was pinned down by this shroom of glass that catches and carnivalizes the sky.

Final yr, Christie's mounted Dress Your Desk, an online auction of dozens of paperweights that had belonged to Arnold Neustadter, the inventor of that other once-ubiquitous desktop accessory, the Rolodex. He was "the near organized man I ever knew," his son-in-law told an obit writer. Adding, "Whenever anyone put something on his desk that didn't belong in that location, he'd move it." Carleigh Queenth, head of ceramics at Christie's, told me, "He had a really lovely collection, including some incredibly rare pieces like a Pantin salamander weight." Merely 20 of those are known to exist, and only extreme talent could have pulled off the forms, textures, and patterns (e.g., polka-dotted amphibian bod on floor of sand and lichen). A prior director of the Corning Museum of Drinking glass, which has assembled one of the most of import exhibitions of paperweights, regards these salamanders every bit "the greatest technical achievements of nineteenth-century paperweight makers."

The French paperweight heyday, betwixt 1845 and 1860, remained the loftier-water mark for the manufacture for nigh a hundred years. So in the sixties, in America, the studio-glass move relocated glassmaking from factories to ateliers, where utility gave mode to fine art. Art schools started to teach glasswork. Galleries started to show glasswork. And Paul Stankard, co-ordinate to Queenth, "was ane of the first contemporary glass artists to drag paperweights to an art course." Stankard is a living master, unrivaled. "While flowers in nineteenth-century weights can be somewhat cartoonish," she said, "his are always incredibly accurate, like botanical studies." She pointed to Stankard's bees. "You lot can practically hear them buzzing."

Paul Stankard, Field Flowers Cluster with Honeycomb and Swarming Honeybees Orb, 2012. Photo: © Ron Farina

When I phoned the seventy-4-year-old creative person at his studio in southern New Jersey, he told me that, under the effect of an eighteen-hundred-degree flame, hot glass is sticky, "similar honey." He had attended a vocational school and begun his career bravado bespoke glass equipment for chemists. "It was a good trade, but I wanted to be creative." He imagined suspending the flowers of Delaware Valley from his babyhood—he's a Walt Whitman devotee—in glass. He drove upwardly to Corning and studied the antiques. In 1972, he left his job to become a full-time paperweight maker. Stankard weights are transcendent. "But you're welcome to put them to work if you want to," he said. "They'll keep paper down."

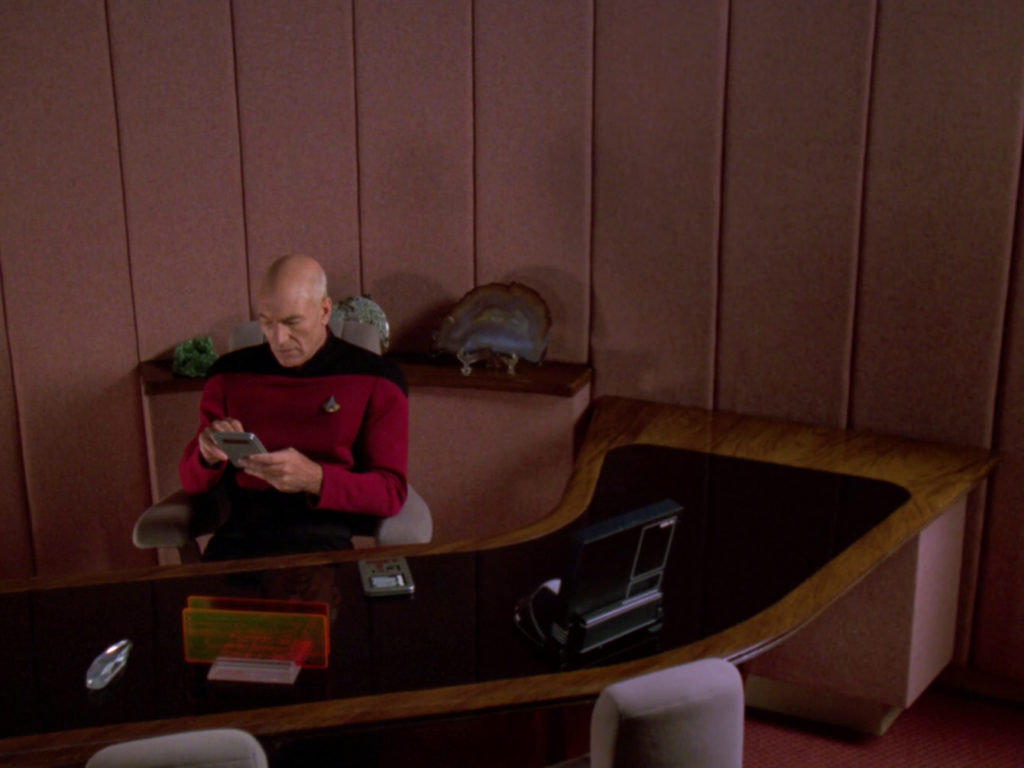

While my paperweight helps me listen the gap between the analogue and digital worlds, perhaps paperweights volition never become obsolete, even in the twenty-fourth century, when human club volition have gone paperless, at least in outer space and co-ordinate to Star Trek: The Next Generation. Yet, it is something to observe a shard-like crystal on the desk of Captain Jean-Luc Picard. The iconic prop appears in nearly eighty episodes. It is not technology. It does zilch—although Picard oftentimes handles it while mulling over tough decisions or speechifying, in such a manner that the crystal recalls Yorick's skull. Trekkers accept painstakingly attempted to re-create the hunk in casting resins. No 1 knows what became of the original from set.

Helm Picard'due south desk in his gear up room on the USS Enterprise-D (1989, or 2365).

Roddenberry Entertainment—named after the creator of the original Star Trek goggle box series—offers a faithful ninety-nine-dollar lead crystal replica on its web store. The prop'southward geometry, the production description says, "was obsessively reconstructed using digital 3-D modeling software, referencing and reconciling hundreds of film frames of the crystal'southward appearances beyond the seasons of TNG." (Ryan Norbauer, a software engineer whose résumé includes stints at NASA, the Middle for Disease Control, and British Parliament, was on the project.) "It'south a great way to add a bit of commanding gravitas to your workspace, whether that'south the ready room of a starship or a tabletop at a café."

Roddenberry's director of consumer products, Brent Beaudette, told me they fabricated a run of five hundred Picard desk crystals. Well-nigh half accept sold since they were released in Baronial. I asked Beaudette if he idea the bear witness's set designers, in imagining the future, might have retained a vestigial paperweight. He said, "Our overall consensus is that it serves every bit a device to save tension or stress through unproblematic repetitive movement. However, we tin can but speculate as to the original intent."

Worrying my weight with my left paw, I thought back to Capote. He traveled with his paperweights in a black velvet bag, taking as many as half-dozen of them, even on 2-mean solar day trips to Chicago. They were a condolement, he explained.

Chantel Tattoli is a freelance journalist. She's contributed to the New York Times Magazine, VanityFair.com, theLos Angeles Review of Books, andOrion, and is at work on a cultural biography of Copenhagen'southward statue of the Little Mermaid.

rodriguezlixed1995.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/09/20/the-surprising-history-of-paperweights/

0 Response to "Why Is It Ironic That Arabs Taught Venetians the Art of Glass Blowing?"

Post a Comment